The Mocking of the Scientific Journal: Part Two

Peer reviewed journals have serious problems, but the first issue of the journal of the newly invented Academy of Public Health shows its new model to be far worse.

The recent launch of a new scientific journal has raised alarms everywhere from Science to Wired to the blogosphere because its editorial board is larded with COVID minimizers and it is backed by the right-wing political publisher, Real Clear Politics. To understand the problems inherent in this model, one need look no further than the Journal’s inaugural content. Let’s take a deep dive the one piece of original public health research in that content, a study of masking in schools in Fargo, North Dakota.

In July of 2022, the Brownstone Institute, lauded a preprint released a week earlier, calling it “The Best Mask Study Yet”. The authors of that study had taken advantage of a natural experiment in which a school district on one side of Fargo had mandated masks while a neighboring school district in West Fargo had not. The goal was to compare differences in rates of diagnosed COVID among students in the two districts over the course of the mandate to the difference in rates after the mandate. So far, so good.

The devil was not just in the details. He held a New Year’s Eve party there.

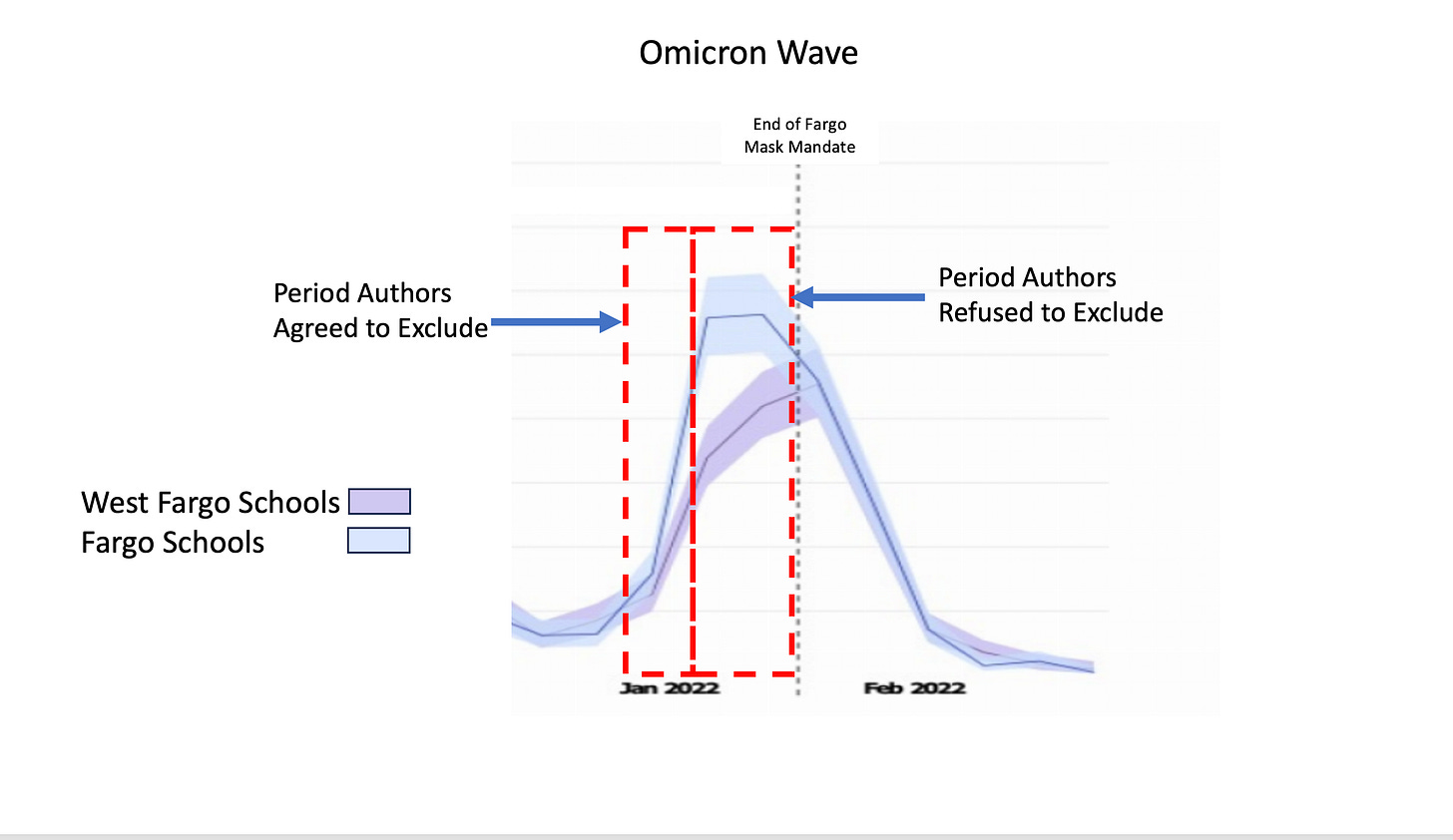

Consider the lone graph from the paper, which shows the rate of COVID cases in the two school districts. The figure is dominated by a huge spike in COVID cases which started in late December of 2021 and extended into January. This spike was seen globally and reflected the deadly convergence of the Omicron Variant , which first appeared in the US on December 1, and lax use of COVID precautions during Holiday festivities.

Clearly, COVID is not spreading in schools when they are closed. Since COVID has an incubation period of 2-18 days, cases initiated during the holidays could continue to appear for at least two weeks after the holidays. But the mask mandate ended exactly two weeks after the Christmas break ended. If one is trying to isolate the contribution of schools to COVID incidence in children, the obvious solution is to end the study period at the beginning of that break.

The original analysis in the preprint includes all data up to January 17, even the vacation. When I saw that, I decided to contact the authors. My first challenge was to pick the author responsible for the epidemiological analysis. Given that the author list includes an economist, a blogger for the Brownstone Institute with a Batchelor’s degree in audio engineering, a self-described “Lifestyle Photographer and Christian Counselor/Life Coach”, and an epidemiologist, the choice seemed obvious. But, when I reached out to the epidemiologist to ask why she had chosen to include the holiday period in a study of school-based transmission, I was, to my surprise, referred to the economist.

I suggested to the economist that they should do a separate analysis of the period prior to the holiday. After exchanging a few emails, he “conceded to excluding data from Dec 25 to Jan 6 to account for holidays”. This exclusion assumes a maximum incubation period of 3 days for COVID, a figure not supported by any of the published literature. He insisted that it would be inappropriate to eliminate any other days because he didn’t want “to exclude valid data”. It is not entirely clear what he meant by valid, but, for some reason, with 114 days of data before the holidays available to analyze, he was clinging tenaciously to just 10 days from January 7-16, after which mask mandates were eliminated. Why?

The number of cases during the Omicron Wave were 5-6 times higher than during the rest of the study period. The period the authors refused to remove just happens to be a period when incidence rates were much higher in Fargo than West Fargo. A closer look at COVID data from Cass County (where Fargo is located) makes it clear that school masking policies probably had little to do with this difference.

The graph below of COVID cases for children, adults, and the elderly, makes two things clear. First, cases did not begin to rise until after Christmas, making it highly unlikely that school-based transmission played any initial role. Second, the rise among adults was higher than and preceded the rise among children. Adults, it appears, were the ones going to parties over the holidays and were the first group to get sick. The fact that they got sick first suggests that many of the cases in children were due to secondary transmission from adults infected over the holidays. This would result in kids getting sick from adults for weeks after the holidays. Most of a child’s exposure to adults happens outside of the schools.

Census data provides a possible explanation for the higher rates of COVID in the Fargo school district. Adults make up a far greater portion of the population in Fargo. If adults are the ones sick from the holidays, being around more of them might well raise your risk.

Schools may have played some role in the transmission of the Omicron wave, but they do not appear to have been the primary driver during the first weeks of January. Trying to tease out any role for the schools during this period would require information on how COVID was spreading in the rest of the community, which is not possible with the available data. The bottom line is that the unique mechanisms of spread were at play during the Omicron wave that could have confounded study results. The authors probably should not have included that period and, at a bare minimum, should have provided a separate analysis without it.

What would the authors have found if they removed the Omicron Wave from their data. First, let’s look at the period prior to the Christmas holiday. Again, the data the authors used are no longer available from the school district, but we can take a rough cut at this analysis by examining their graph. The graph suggests that for most of the Fall (11 of 15 weeks), COVID incidence in West Fargo schools exceeded Fargo Schools. Think of this as flipping a coin and getting heads 11 of 15 times. There is less than a 5% chance that could happen with a fair coin, i.e. if there were no difference between the school districts. In other words, a proper analysis of the pre holiday data appears likely to have shown that masks worked.

The study compared 124 days of data with the mandate in place to just 28 days after the mandate was removed in Fargo. This makes the authors’ objections to excluding a ten day window somewhat less than compelling. Apparently, 28 days was plenty of time to study differences with no mask policy, 114 days was not enough to study the period when mandates were in place. It would actually have been a good idea to have more days of “valid data” from the period after the mandate was lifted, especially when the period they used from after the mandate is the tail of the Omicron wave, not exactly the most representative data. Nonetheless, even during the brief period they considered after lifting the mandate, the lines for the two districts are almost on top of each other. Overall, the data appear to show that COVID incidence in Fargo schools was lower than West Fargo while mask mandates were in place, but did not differ after the mandate ended.

To recap, the “best mask study ever”, relied on a ten day stretch of data with a spike in cases five times higher than average, driven by events that happened during a school vacation, to drown out what appears to be the protective effect of masks and draw the conclusion that masks provided no protection from the spread of COVID. When I suggested that the authors remove those ten days from their analysis two and a half years ago at the time their preprint was released, they refused to do so. Since then, it seems likely that any peer reviewer to whom they sent the study also asked them this question. It would be obvious to most epidemiologists. It is a near metaphysical certainty that the authors tried this, but didn’t want to share their findings. So, the paper remained stuck in preprint purgatory. The only solution was an entirely new kind of journal, ideally one that didn’t require peer review.

They wanted credibility for this flawed paper that had been rejected by peer reviewers for two years and others like it. To do that, they and their colleagues needed to invent, not simply a journal, but an entire Academy of Public Health.

The Academy of Public Health did not exist until a month ago and it barely exists now. As of this writing, a week after the launch of the Journal of the Academy of Public Health, even Google doesn’t know that the Academy exists. A search for it points to an organization in West Africa that actually does public health. Currently, this looks like an insider’s game. In fact, the Journal, in many ways, is the Academy. The Academy’s bylaws state that, “Any member of the Journal Editorial Board may invite prominent public health scientists as new members of the Academy by sending a written invitation to join the Academy.” According to the Editor and Chief of the Journal, members are accepted if existing members consider them to be “good scientists,” which they establish “either by knowing it already from our own experience as scientists, or by reading what they have published”. Members can then publish without peer review.

I will have more about the Academy of Public Health in a later post, but, suffice it to say, that this single paper serves as an indictment of both the Academy and the Journal it spawned (or is it the other way around). If this “journal” was intended to bring credibility to this kind of research, then, as a serious research publication, it is dead on arrival. Far worse than that, it creates further confusion among the non-scientific community as to what is a credible source of scientific research.

In an editorial written for the launch of the Journal of the Academy of Public Health, editor-in-chief Martin Kulldorff makes a compelling case that the current model for scientific publishing is profoundly broken. The journal proves that case by showing how easy it is to create something even worse.

Truly tragic.

I know it´s no comfort, but following my Comment to your Previous: Part 1.

Nothing new there.

Robert Whitaker in Mad in America, together with an expert delving into the data of the original study on some antidepressant has been vociferous about the denial, concealment, etc., by the researchers of his critiqued study. Funded I think by NIH grants, but I might wrong on that one.

Peter C. Gøtzsche has suffered a lot in his fight against Bad Science/Bad Pharma, and has narrated his struggles, some in Mad in America, I guess some on his website.

Perhaps to be propositive there needs to be criminalization of such Fraudulently published research, specially when done with public funds like NIH grants.

Or at least there should be an administrative law mechanism to withdraw those articles that do not even pass the Smell Test.

Some fake results even reached an appelate court on the US and probably the Supreme Court on abortion. With similar unqualified "experts" if I am not remembering incorrectly "writing" them.

As I said in my previous comment to your Part 1, there is History there and I think it should be made clearly, specifically illegal to publish such research. Maybe even criminally so.

But I am not a lawyer and not giving advice, nor advice of any kind.