How COVID Broke Stanford and How Stanford Broke Science: Part 1

The party for purveyors of misinformation

Note to readers: This post now includes both part one and part two from the original posts on How Science Broke Stanford)

On October 4, Stanford will be holding what the LA Times has called “a party for purveyors of misinformation and disinformation about COVID”. This is not mere hyperbole. In a pandemic that has seen a flood of falsehoods, Stanford has allowed a few members of its faculty to play a leading role in offering the patina of scientific credibility to fringe ideas. Now, that university’s President is set to preside over a symposium, entitled “Pandemic Policy: Planning the Future, Assessing the Past” featuring a line up of speakers, including faculty from other top universities, with a record of wildly underestimating the seriousness of COVID and not admitting error when reality proves them wrong. The event makes a mockery of the universities as seekers of truth. To fully understand its implications we need to consider how Stanford and science got to this point.

To understand the public health perspective on COVID, we need to go back over 20 years to the first time a deadly coronavirus made the leap from wildlife to humans. What came to be known as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) emerged in southeast China and would ultimately spread to 28 countries, killing 15% of everyone infected. Had this disease become a full-blown pandemic, it would have made COVID look like child’s play. Instead, you may not have even heard of SARS. That is because two years of aggressive public health measures, including isolation, contact tracing, high efficiency masks, quarantines, and travel monitoring, contained and ultimately eliminated the virus.

When COVID began to claim its first victims in Wuhan, it gave serious epidemiologists and public health practitioners a horrifying sense of déjà vu. They were well aware of SARS and the pandemic that didn’t happen. When COVID-19 began to spread and kill around the world, they pushed hard for aggressive public health measures.

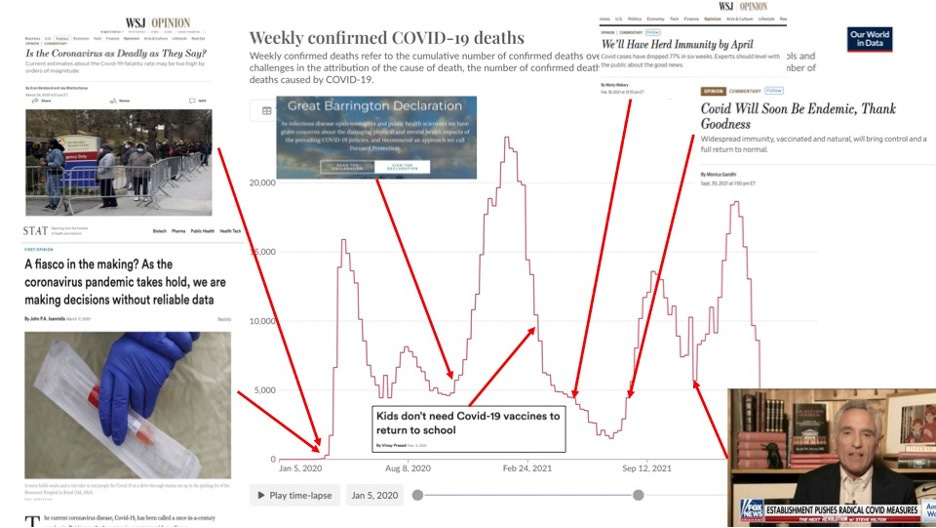

Stanford economist, Jay Bhattacharya, wasn’t so sure that was necessary. He thought this second version of SARS was more like swine flu, which struck in 2009 and proved to have an infection fatality rate (IFR) far below initial estimates. This belief that COVID could be managed with minimal intervention was so politically and financially compelling that, by the time the virus proved it wrong, it had generated a massive global following and would make Stanford a hub for pandemic misinformation. The October conference marks the culmination of that story. The path began not with research in support of opinions but with opinions demanding research, a recipe for bias.

Two economists and a hedge fund manager walk into a pandemic

In March of 2020, just two days after Donald Trump declared COVID to be an emergency, Neeraj Sood, a USC economist argued in the Wall Street Journal (WSJ) that COVID might be no worse than the flu. That was followed in short order by an opinion piece from Stanford physician, John Ioannidis, suggesting measures to contain COVID might be a “fiasco in the making” and that we might see 10,000 deaths from COVID. Bhattacharya and his former student, Eran Bendavid, joined this chorus with another WSJ opinion piece that surmised there had already been six million cases of COVID in the US, more than 100 times the reported number, and only 0.01% of them had died, roughly one tenth the mortality of seasonal flu. The fact that all four of these writers wound up doing a study together to prove their point does not feel like a coincidence.

There was nothing particularly newsworthy in the call for more data. What stands out here is the willingness of these authors to speculate on risks in the absence of those data. The epidemiological community was painfully aware that we simply didn’t have enough tests to evaluate every potential case. But few of them believed that COVID was not a serious threat to public health or sought to share the idea through Rupert Murdoch’s megaphone. The virus would prove these estimates to be laughably wrong, but their consequences were deadly serious.

The Santa Clara Study: The birth of “no worse than the flu”.

Neither Bendavid nor Bhattacharya are epidemiologists by trade, but nine days after publishing their op-ed, they, together with Ioannidis, Sood, and a hedge fund manager, had assembled a team that was collecting blood at stations around Santa Clara county and testing it for antibodies to the COVID virus. The fact that no one on the team had ever conducted a seroprevalence study is clear in their apparent blindness to what epidemiologists refer to as selection bias.

Selection bias happens if the motivation for participating in a study is related to what you are measuring. Avoiding it is the single biggest challenge in a seroprevalence study. To understand why, imagine it is April of 2020 and you see an ad on Facebook about a study “to determine how many people in our county have had COVID”. To participate, you will need to violate a stay-at-home order, drive across the county and give blood. The simple question is, will you be more likely to participate if you have been sick? If so, there is a problem. As evidence of their blindness to this problem, Bhattacharya was unphased by the fact that his wife sent an email to parents at their child’s school explicitly encouraging them to get tested if they thought they or anyone they know might have been infected suggesting they could learn if “they no longer need to quarantine and can return to work without fear”. His only concern seemed to be that they had oversampled this area, not that they had oversampled people with a history of illness. This is selection bias on steroids.

There are many techniques employed by experienced epidemiologists to reduce selection bias and to test for its presence. Ioannidis was the lone epidemiologist on the team, but his career had been built on reviewing and critiquing the work of other epidemiologists. Even the best film critic cannot be counted on to make a great movie. He had little experience in doing original epidemiology and had never done a seroprevalence study. So, they did almost nothing to address selection bias. They also chose to ignore warnings from two Stanford scientists that their antibody test might not be accurate. The authors waved off these concerns, but, given their multiple, very public, proclamations of their expected findings, one wonders if they were falling prey to a biaswarned about by Ioannidis himself. “Scientists in a given field may be prejudiced purely because of their belief in a scientific theory or commitment to their own findings.”

Apparently, none of this occurred to the authors or made them skeptical of their findings. They took their data suggesting COVID killed less than one in 500 people infected, similar to seasonal flu and ran with it. Their campaign to disseminate and promote this finding began before they had even written up the results.

First word of the study appeared just two days after they completed sample collection, not in a scientific forum and not from the study authors, but from the CEO of Jet Blue, David Neeleman. This is bizarre in the extreme. Neeleman’s motivations are clear. He was concerned about the travel bans that had effectively shut down his airline. The authors of the study declare no conflict of interest and insist Neeleman had no impact on the study, Neeleman himself stated he had been in regular contact with the three main authors and provided $5,000 to support their research. He had even told them that Elon Musk would be interested in funding a much larger, national study. The fact that he was the first to publicly announce their work provides clear evidence that his role was anything but hands off.

Public Health tends to operate on the precautionary principle, the idea that, in the face of uncertainty, you use worst case assumptions to make decisions to protect public health. These authors seemed determined to apply the precautionary principle to protecting the economy. Despite serious doubts raised by colleagues at Stanford, they rushed the results to the public, releasing the study as a preprint just two weeks after collecting samples.

Bhattacharya has suggested this was a routine choice, but use of preprints in Medicine was anything but routine. Preprints were not new to science. In fact, the first world wide web server in the United States was a preprint server for physicists. But the preprint server for medical science, medrXiv.org had only existed 10 months and Bhattacharya had never released a preprint before. Preprints are a great innovation, allowing for the immediate release of research results, a vital function during COVID, but there use in this case meant that there had been no opportunity to critique the study before its conclusions were shared with the world. And the authors did everything they could to make that happen. They appeared everyplace from CNN and Fox toYouTube. The hedge fund manager on the team penned an op-ed for the Wall Street Journal. Again and again they declared that COVID is no worse than the flu. They were wrong.

One other organization that picked up on their work was the American Institute for Economic Research, which published an extended piece lionizing John Ioannidis and welcoming his findings. This connection would grow to have major implications for the management of the pandemic and begin to define the arc that would lead to the Stanford Pandemic Symposium. But first there would be a key stop, the Oval Office.

Redefining expertise: Atlas moves the world

The conservative Hoover Institute, housed in the most prominent building on the Stanford campus, has two physicians among its senior fellows. Jay Bhattacharya and a neuroradiologist by the name of Scott Atlas. On March 24, Atlas joined the chorus responding to the results of the Santa Clara study by publicly declaring that we were in the “containment phase” of the pandemic and efforts to limit the spread of COVID were part of the problem because they were preventing us from reaching “vital population immunity”. Astonishingly, he wrote this at a time when more than 300 Americans were dying every day and refrigerator trucks were parked outside New York City Hospitals to house the dead.

One of the first people to publicly insist that COVID was no worse than the flu, was Donald Trump, who tweeted on March 9 of 2020 that only 22 people had died from COVID compared to the “37,000” flu deaths in the previous year (a nod to his loose relationship with facts since 27,000 Americans died in the 2018-2019 flu season).

Six weeks later, when Atlas wrote his opinion piece, this argument was already falling apart. By August, COVID had killed 175,000 Americans and was adding 1,000 per day to that total. But Trump chose that moment to name Atlas as his newest COVID advisor.

Given the President’s access to world class expertise on infectious disease, public health, and epidemiology, Trump’s choice of Scott Atlas reveals he did not care about genuine expertise. There are few fields of medicine farther removed from those relevant to COVID than neuroradiology. In fact, none of those three terms appears anywhere in Scott Atlas’ 150 page CV. Atlas did, however, offer two things. Compelling conclusions and plausible credibility. The irrelevance of his training to the problem at hand didn’t matter if he could appear on Fox News with Stanford and an MD next to his name.

The Great Barrington Declaration: Making Public Health Interventions the Problem

Few true subject matter experts supported the notion that the best strategy to protect people from COVID was to allow them to become infected. There was, however, one notable exception, a pioneer of the strategy, Swedish Public Health Minister, Anders Tegnell. In April, when Scott Atlas wrote his opinion piece urging a strategy of “focused protection” for the most vulnerable (the elderly, the ill, and the immune compromised) and immunity through infection for others, Sweden had been practicing it since the outset. It wasn’t going well. With more than four times the COVID death rate of its nearest neighbors, Norway and Finland, Tegnell doubled down.

Sweden, Tegnell claimed, was “already seeing the effect of herd immunity and in a few weeks’ time we’ll see even more”. The basis for this belief is not clear. Herd immunity happens when there are enough people with immunity in the population to prevent exponential growth of infections. Perhaps he was drawing on the conclusions of Bhattacharya about infection rates and presuming enough people had been infected to get them there. Whatever the reason, over the next three months COVID deaths in Sweden more than doubled, reaching roughly ten times the rate of its Nordic neighbors suggesting both he and the Santa Clara Study had been wrong. Even Tegnell acknowledged they could have done better and before the end of the year, Sweden had to institute many of the mitigation measures they initially resisted.

Then, the flood of COVID deaths in Sweden ebbed. This probably had much more to do with the Swedish summer than herd immunity, but it helped fuel the belief that the Swedish strategy was working. The American Institute for Economic Research (AIER), which had lionized Ioannidis, seized the moment. In October, they invited Jay Bhattacharya, Martin Kulldoorf, then a Harvard biostatistician, and Sunetra Gupta, an Oxford theoretical epidemiologist, to their headquarters in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, to craft a statementadvocating that governments adopt the strategy advocated by Tegnell and Atlas. Because they believed that immunity to COVID was long-lasting, The Great Barrington Declaration (GBD) claimed that the mass infection of “not vulnerable” people, none of whom were vaccinated at the time, would lead to herd immunity and end the pandemic in 3-6 months.

The Great Barrington Declaration (GBD) prompted two reactions, derision from most subject matter experts and invitations to the White House to discuss their recommendations with Atlas and Trump. Several of the authors had already had a “secret meeting” with Trump in August 2020. The document itself is only a single page with little specificity, reflecting dangerously simplistic thinking, but it created a banner that drew denialists of all stripes. The next four months saw the worst spike in COVID deaths of the entire pandemic.

COVID Denialism Meets the Anti-vaccine Movement

In March of 2024, Robert F Kennedy junior held a rally to announce his vice-presidential selection. Kennedy, the poster child for the anti-vaccine movement, had been spewing deadly misinformation for over a decade. The public health community was shocked to see Jay Bhattacharya at the podium , lending the credibility of Stanford to this dangerous voice. The disturbing transformation from minimalizing COVID to implicitly attacking vaccines bears scrutiny.

The reasons for this shift are buried in the logic of the GBD. Epidemics end either with aggressive public health interventions, as happened with the SARS Epidemic, or through the emergence of herd immunity. There are only two paths to immunity, infection or vaccination.

Absent a vaccine, the Great Barrington/ Swedish Strategy might have made some sense. The arrival of the first COVID vaccine in November of 2020 made it look foolish. For their strategy to continue to be right, the non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) and vaccines had to be both dangerous and ineffective.

The same forces that had turned politics into a blood sport was infecting the public debate over the science. The relatively small group of scientists who aligned themselves with the GBD perspective knew how to pull the levers of academia and science publishing to deliver scientific support. Those who supported their libertarian version of public health amplified them on conventional and social media.

The Myth of More Harm than Good

One might reasonably expect a declaration by an economist, coordinated by an economic research organization, to discuss economics. We certainly needed to be asking ourselves if the public health benefits of interventions were worth the economic impact of stay-at-home orders, travel bans and closures of businesses and schools. Instead, all these economists wanted to discuss was epidemiology. There is a reason for that. Arguments about financial costs outweighing saving human lives are never popular. If you can get the epidemiology to say COVID is “no worse than the flu”, you don’t have to make the economic argument because we, as a society, have implicitly decided we don’t need to intervene for seasonal influenza. Similarly, flawed epidemiology became the tool to say public health interventions from masks to school closures don’t work and may cause more harm than good. The worst such studies were reserved for vaccines and the most egregious of these was a specific vaccine cost-benefit study.

Vaccine mandates pose a significant ethical question if the vaccine poses a risk to the recipient. In the 2021, evidence emerged that COVID vaccine was, in rare cases, causing myocarditis, a serious but transient inflammation of the heart wall. There is clear evidence that the risk of myocarditis and more severe heart conditions are higher from COVID than the vaccine, though COVID’s harms are not limited to the heart, and seems likely that those reacting to the vaccine would react even more severely to the virus. However, any vaccine risk raises ethical concerns.

In December of 2022, the Journal of Medical Ethics published a discussion of ethical questions related to vaccine mandates for young men. In a bizarre departure from the journal’s typical content, the paper included a risk/benefit assessment of the COVID vaccine in this population based on the available epidemiological evidence. The conclusion from that study had been anticipated by the lead author, Kevin Bardosh, a medical anthropologist, who had declared in an opinion piece ten months earlier that vaccines, “may cause more harm than good”. The team he brought in to do the epidemiology included Marty Makary, a transplant surgeon from Johns Hopkins who had declared in a WSJ opinion piece that the US would achieve herd immunity by the Spring of 2021, and Vinay Prasad, a UCSF oncologist who had equated COVID public health interventions with the actions of Hitler’s fascists, suggesting they could end democracy.

The study was a veritable fruit salad of cherry picking and apples-to-oranges comparisons that could only pass muster in a journal totally inexperienced in publishing original epidemiology. Its conclusion, as Bardosh had predicted, was that the vaccine does more harm than good and does nothing to limit transmission. What this meant was the ethical discussion was largely moot. The only reason for vaccine mandates is to limit transmission and if they pose greater risk than benefit to the recipient, there is no serious ethical debate. Like the economists, the ethicists had avoided difficult discussions by torturing the epidemiological data until it confessed.

Which Brings us to Stanford

With the pandemic fading but still fresh in our minds, this may be an appropriate moment for a symposium entitled, “Pandemic Policy: Planning the Future, Assessing the Past”, hosted by an elite university and bringing together leading experts representing the range of perspectives to consider the weight of the evidence. Instead, on October 4, not coincidentally the four year anniversary of the GBD, Stanford will cement its position as the epicenter of COVID denial by bringing together eight of the self-declared experts listed above at a conference organized by Dr. Bhattacharya. Joining them will be Jenin Younes, a lawyer who helped plan for the GBD, Monica Gandhi, an infectious disease specialist who repeatedly made horribly wrong predictionsabout COVID, and Laura Kahn, a physician whose relevance appears to be a forthcoming book blaming COVID on a lab leak. Not one of the presenters represents mainstream scientific viewpoints, and most of them never treated a COVID patient themselves.

Certainly, dissident voices should be heard, but Stanford has turned this equation on its head with a conference exclusively devoted to speakers whose assessment of COVID diverges completely from the consensus of subject matter experts and whose predictions about COVID have proven repeatedly and often dangerously wrong as laid out by others in excruciating detail.

To add an exclamation point to the lack of self-skepticism that pervades this conference, its closing speaker, John Ioannidis, has been extremely vocal in his concern about the need to hear from all perspectives. He just published a paper complaining that a panel assembled in 2022 to assess the science and policies related to COVID was “stacked”. In particular, he complained that too many panel members were associated with the Zero-COVID movement. These groups had no formal statement of perspective, but supported minimization of COVID cases, primarily through aggressive intervention to crush the epidemic followed by isolation, contact tracing and quarantine to limit spread of new cases. This is literally textbook epidemic control. The textbook may not always be right, but one should at least be aware of what it says. It was the method used against major outbreaks such as SARS, MERS, and Ebola. By 2022, it was clear that we were not going to eliminate the disease and only 18% of the 655 panel members were associated with it. Apparently, that was too many for Ioannidis.

As he closes an event populated almost entirely by proponents of a single viewpoint, one wonders whether Ioannidis will be reflecting on his professed concern for representation of a full range of scientific perspectives. Unfortunately, self-reflection and self-skepticism is in short supply at this symposium. Perhaps, he should go back and read his best known paper, one of the most cited papers of all time, “Why Most Published Research Findings Are False”. Among its many caveats is one that seems remarkably apt for this moment:

The greater the financial and other interests and prejudices in a scientific field, the less likely the research findings are to be true. – John Ioannidis

How Did This Happen and What Can We Do About It?

Normally, the wheels of science grind slowly and in relative isolation, making their way across a long arc that bends towards the truth. This system struggles in the face of any of four conditions: 1.) Urgency, 2.) Vested interests threatened by those truths, 3.) Intense interest from non-scientists, and 4.) Science that is complex, interdisciplinary, and heavily reliant on observational studies. The COVID crisis elevated all of these conditions to the extreme, overwhelming every system in place to ensure that the highest quality science reaches the public and informs public policy. Scholarly journals, scientific and medical societies, government agencies, and the conventional media failed to stop the deadly flood of misinformation. Social media and political forces amplified it to a scream. Now, it seems, even the universities are complicit.

In the Trumpian, post-truth world, we may have become inured to misinformation, but the fact that leading academic institutions, the supposed seekers for and guardians of the truth, have been coopted in this manner should set off an ear-splitting alarm throughout the scientific and academic communities as well as the government agencies that depend on their work. Top level organizations such as the National Academies of Science Engineering and Medicine, the National Science Foundation, and the American Associations for the Advancement of Science as well as individual scientific societies must take notice and develop plans to address the following needs:

1. Provide systems to capture the assessment of emerging research by expert communities in real time. Peer review is a plodding, archaic, deeply flawed, and easily manipulated system dating to a time when mailing photocopies represented cutting edge technology.

2. Provide absolute transparency on research funding and develop checks to ensure that private funders can’t influence study results or promote the careers of researchers whose findings appeal to them.

3. Create powerful disincentives within universities for knowingly spreading misinformation.

4. Build online fora for the scientific community to discuss and debate emerging science in real time. Attempts to control misinformation on public social media have backfired, allowing its purveyors to cry censorship. Instead, the scientific community must take tools that power social media and use them to foster meaningful scientific debate and discussion.

The forces that have given us the Stanford symposium threaten to undermine the effectiveness of our response to the next pandemic, but they represent a larger trend that is even more worrisome. The normalization of scientific misinformation poses an existential threat to the quality and credibility of all the science that supports public policy, particularly as it relates to protecting public health. In this world of alternative facts, truth has become fungible, something determined by likes and followers rather than any objective criteria, a prize offered to the owner of the biggest megaphone. This particular megaphone is decorated with a large, red S.

The original agenda for Stanford’s October 4 symposium, “Pandemic Policy: Planning the Future, Assessing the Past” brought to mind images of an internet misinformation silo made flesh. The LA Times called it “a party for purveyors of misinformation and disinformation about COVID”. The featured speakers’ past predictions about COVID proved repeatedly and often dangerously wrong. Now things have gone from bad to bizarre and Stanford seems to have declared itself the epicenter for fringe pandemic science. (Go here for my post on the original agenda.)

Perhaps in response to these criticisms, the organizers took the extreme step of entirely reorganizing the agenda, more than doubling the number of speakers, announcing the changes just a week before the event. A review of the new speakers reveals that, rather than add subject matter experts to provide balance, they simply expanded the number of denialists, perhaps imagining that adding enough contrarian voices would foster the illusion of consensus.

Thanks for reading Behind the Science, Ahead of the Curve! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Consider those additions.

· The orginal agenda did not include the media, but these new voices hardly suggest balance:

o Jan Jekielek, an editor from Epoch Times, a publication associated with Falun Gong that recently came under investigation for money laundering.

o Alex Berenson, an anti-vax influencer once called “the pandemic’s wrongest man”,

o Wilk Wilkinson a self declared Christian conservative and “blue collar sage” who has no science background, and

o Gardiner Harris is a NY Times political reporter who does not appear to have written on COVID, but has written an exposé on Johnson and Johnson.

· The Editor for the NEJM AI is included for reasons that are not immediately clear.

· Four members of Biosafety Now, an organization led by an artist, a physics graduate student, a geneticist, and an economist which asserts that “a research-related spillover almost certainly led to the COVID-19 pandemic.”

· A mathematical biologist who has been a relentless proponent of the lab leak theory.

· Three economists, including the symposium organizer, Jay Bhattacharya.

· Four Stanford professors

o A psychologist with an expertise in aging who will be opening the symposium,

o A health services researcher with expertise in assessing clinical interventions,

o A political scientist with a focus on health policy, and

o A lawyer and fellow of the right wing Hoover Institute (one of three on the agenda).

It seems as if the organizers explicitly avoided (or were avoided by) genuine subject matter experts, even those on their own campus. Stanford faculty have published more than 2,000 scientific papers on COVID. Stanford hosts a national network for detecting potential pandemic viruses in wastewater led by engineering professor, Alexandria Boehm. Infectious disease epidemiologist, Jade Benjamin-Chung, co-authored a pivotal randomized control trial of community level masking that demonstrated their effectiveness in reducing COVID transmission. A query to Chat-GPT for experts in infectious disease epidemiology at Stanford returns seven world authorities. None of these scientists are at the symposium. Even experts on COVID testing, Taia Wang and Scott Boyd, whom Jay Bhattacharya sought out for his flawed seroprevalence study were excluded, perhaps because they advised him not to do the study.

Closing remarks will be offered by Stanford epidemiologist, John Ioannidis. One wonders whether he will reflect on his professed concern for representation of a full range of scientific perspectives. In a recent paper, he and his coauthors complain that a panel assembled in 2022 to assess the science and policies related to COVID was “stacked”. In particular, he expressed concern that too many panel members were associated with groups advocating for “zero-COVID”, which has no formal doctrine but seeks to minimize of COVID cases, primarily through aggressive intervention to stop outbreaks followed by isolation, contact tracing and quarantine to limit spread of new cases. These are literally textbook epidemic control methods, which were used against major outbreaks such as SARS, MERS, and Ebola. Only18% of the 368 panel members were associated with it, but that was apparently too many for Ioannidis.

Unfortunately, self-reflection and self-skepticism appears to be in short supply at this symposium. Perhaps, Ioannidis should go back and read his best known paper, one of the most cited papers of all time, “Why Most Published Research Findings Are False”. Among its many caveats is one that seems remarkably apt for this moment:

The greater the financial and other interests and prejudices in a scientific field, the less likely the research findings are to be true. – John Ioannidis

In this case, the financial interests lie with those threatened by public health measures. The prejudices lie with researchers who repeatedly appeared in the media minimizing the threat posed by a disease that killed more than 1.2 million Americans.

The forces that have given us the Stanford symposium threaten to undermine the effectiveness of our response to the next pandemic, but they represent a larger trend that is even more worrisome. The normalization of scientific misinformation poses an existential threat to the quality and credibility of all the science that supports public policy, particularly as it relates to protecting public health. In this world of alternative facts, truth has become fungible, something determined by likes and followers rather than any objective criteria, a prize offered to the owner of the biggest megaphone. With the University’s President presiding, this particular megaphone is officially decorated with a large, red S.